Valkenburg Airbase and the Flood Disaster of 1953

In the night of January 31 to February 1, 1953, a sixth part of The Netherlands was inundated by the North Sea. In the days that followed, Vliegkamp Valkenburg played an important role in the relief effort. Jaap Dubbeldam wrote the following article about this.

On Saturday evening the 31st there was a storm on the Dutch coast. The weather service issued a warning for a north-westerly storm, wind force 9. During the night, the storm increased to wind force 10 and cleared to the north. The storm was at its peak on Sunday morning. At Vlissingen and Hook of Holland the wind speed rose to more than 120 km/h: wind force 12, hurricane. At the same time, there was a spring tide that night: shortly after midnight, the water level at Hook of Holland was no less than three meters higher than normal.

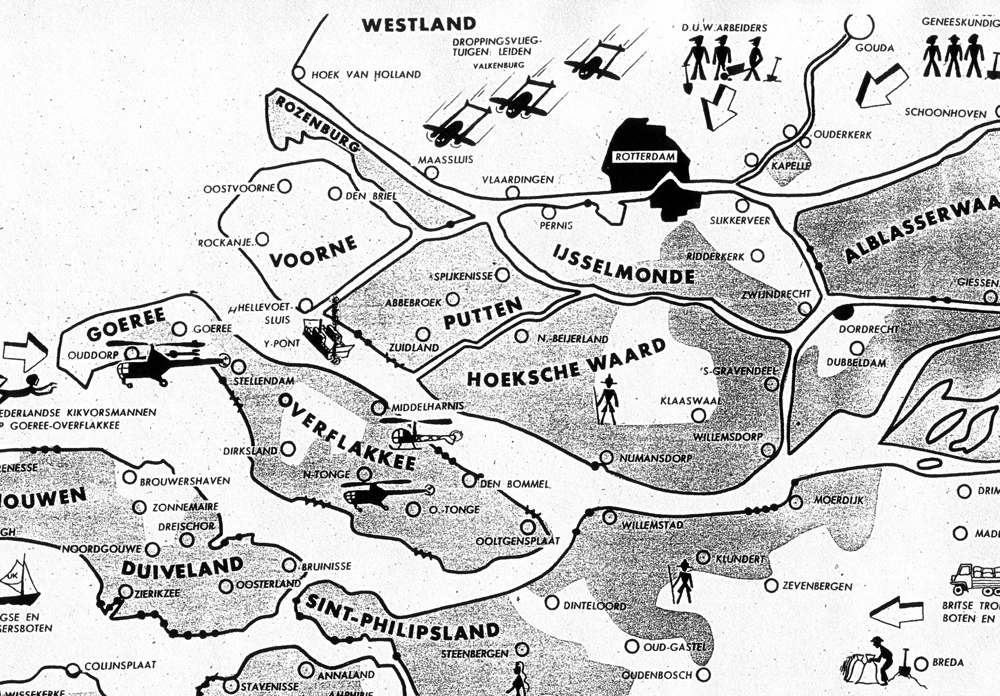

The combination of severe storms and spring tides led to 89 dike breaches and some 500 minor breaches, which flooded some 141,000 hectares of land. A number of Zeeland and South Holland islands and parts of North Brabant and South Holland were inundated. Nearly 49,000 homes and farms were affected. More than 100,000 people were evacuated. The disaster was fatal for 1,835 people.

It was only in the course of the afternoon that the scale and seriousness of the disaster became really clear. A Belgian Hiller helicopter, piloted by a Sabena pilot, was first above the disaster area. He took off from Brussels airport at 4 am with the vague order to rescue 12 people at Overflakkee. When he landed in Oude Tonge at six o’clock, he had seen 1000 people on roofs and in trees. He had managed to orientate himself above the vast body of water by counting the church towers.

After it became known that large parts of the Netherlands were under water and that those areas were inaccessible, a Dutch reporter came up with the idea to view the disaster from the air. For a lot of money he arranged (on behalf of his newspaper) a Dakota from KLM. Above the disaster area they made historical recordings of the flooded polders, destroyed villages and people on roofs.

On Sunday morning, February 1, Valkenburg looked sad. A few bicycle racks with shelter had been blown away by the wind and were found in the nearby bulb fields with bicycles and all. Some rickety wooden barracks of 860 squadron had fallen over. An emergency center was set up for Operations in the flight service building. It was very busy there during that stormy night and on Sunday morning. At half past nine in the morning, all staff received a call to come to the air base.

Immediately on Sunday, government agencies made the first preparations for a large-scale rescue operation. In the night of 1 to 2 February, the deployment was coordinated by the navy, land and air forces. Valkenburg airfield was designated as a center for air assistance.

The operation from day to day

Sunday February 1

As early as Sunday morning, the Mitchells were put on standby and the crews of the Harpoons, Sea Furys and Fireflys were told to remain available. Over the course of Sunday, air base personnel had prepared 13 planes for relief. These were four Harpoons, three Mitchells, two Oxfords and four Dakotas. At four o’clock in the afternoon, the airport was fully operational for flight operations.

It was still storming from the north. There was a crosswind of 50 knots on the main runway. However, an urgent request for help had been received from the mayor of Middelharnis. Two Mitchells from 5 squadron then made their first flight, mainly over Flakkee (island) and West Brabant. They used one of the old runways, probably the 03/21, which still consisted of perforated steel plates. The Mitchells managed to drop three dinghies near Oude Tonge before dark.

The three bright yellow Sea Otters of 8 squadron were put on standby that Sunday and the only helicopter of the MLD, S-51 ‘Jezebel’ was also prepared. The helicopter started up in a hangar, but as soon as the rotor blades came out, they started to whip so violently that pilot Rudi Idzerda had to give up his attempt.

Monday February 2

On Monday, aid started to get underway from Valkenburg. The entire staff had been called up and deployed to load the planes with relief supplies and medicines. That day, the S-51 was the first to see action. The Jezebel flew to the disaster area early in the morning to rescue 45 people from roofs of flooded houses that first day. The following days, the Jezebel operated from Woensdrecht Air Base, because it was closer to the disaster area.

Two Sea Otters also came into action that Monday. The aircraft made the first landings on the flooded polders between Oude and Nieuwe Tonge and brought 27 people to safety. The people were often taxied to a dry area, while the wounded were flown to Valkenburg. During the many flights over the disaster area, these amphibians have rescued a large number of people from their perilous positions.

When a Sea Otter was unable to reach the victims itself, the Harpoon, which served as a liaison aircraft over the area, was contacted. A helicopter was then directed from this plane to the scene. The Harpoon was also the link between the Operations Office at Valkenburg and the aircraft and helicopters operating above the disaster area. On Monday, a Harpoon also ejected 15 dinghies at Stavenisse, among others. An Oxford flew over the affected area with two engineers to determine the places that needed help most urgently.

The four airworthy Dakotas of the Netherlands Air Force were also fully deployed for the dropping flights. It was the technicians who pushed out food, dinghies, medicines, sandbags, clothing and boots from the back door. Two KLM Dakotas also flew from Valkenburg on Monday to drop off dinghies and food.

A total of 48 flights were carried out from Valkenburg on Monday 2 February, during which 40 dinghies, dozens of containers with fresh water and several hundred kilograms of food were dropped.

Tuesday February 3

From Tuesday, the aid became more and more extensive. Aid workers entered the disaster area on hundreds of ships, and where possible also by road. They managed to evacuate many victims from the disaster area. Planes dropped sandbags, rubber boots and dinghies on a large scale. All this was coordinated from the ‘dropping office’ at Valkenburg. From half past eight the Sea Otters, Mitchells, Harpoons and Dakotas took off from Valkenburg. Food and empty sandbags were dropped from the Harpoons. During one of the first flights on February 3, it turned out that this was not entirely without risk, when a sandbag got stuck to a stabilizer of an Harpoon. This made the aircraft less controllable and it vibrated quite a bit, especially at low speeds. With a high-speed landing, the pilot was able to land the aircraft safely at Valkenburg.

The 11 aircraft of the MLD did a very useful job, as they also directed the helicopters to emergencies. This day, a Sea Otter got stuck behind a net hidden beneath the surface of the water.

In addition to Valkenburg, flights were also flown from Schiphol and Gilze-Rijen. In the afternoon about 150 aircraft were in continuous action. The first American aircraft had already arrived at Valkenburg. The press was invited to the airfield to photograph the loading of a C-119C Flying Boxcar. American C-47 Dakotas and HU-16 Albatrosses also took part in the rescue operations from Valkenburg. According to the Nieuwe Leidsche Courant of 4 February, the American armed forces had meanwhile sent seven transport aircraft, 15 liaison aircraft and 18 helicopters.

Two Dakotas from the Norwegian Air Force with blankets and a Catalina from the Danish Air Force with auxiliary material also arrived at Valkenburg on Tuesday. KLM sent a third Dakota and the National Aviation School in Eelde sent four Beechcraft Navigators to Valkenburg. Two Navigators of the LSK stationed at Leeuwarden were also flown over to Valkenburg.

The number of relief flights from Valkenburg on 3 February amounted to 80 and they were carried out with 31 aircraft. The MLD took care of 40 of these flights with a combined flight time of 64 hours. A total of 124 aircraft and helicopters were available for the rescue flights on Tuesday evening. The number of helicopters was 15, including three American, nine British, two Belgian and the MLD Sikorsky S-51. 13 helicopters were still expected from the US military and the UK.

Wednesday 4 February

Aid from abroad got off to a good start on 4 February. Various NATO countries sent soldiers and equipment, and fundraising campaigns were held all over the western world. Two Dakotas from Norway arrived at Valkenburg with blankets and clothes, and a B-17 Flying Fortress with more than 50 dinghies on board arrived from Denmark.

The droppings carried out by the aircraft of the MLD and the Netherlands Air Force during the first days were mainly carried out by the American Flying Boxcars from 4 February. The number of C-119s was expanded with two extra aircraft. The prototype of the Fokker S.13 was also used on this day for an assignment to eject medicines over Walcheren.

The wind was still blowing that day and visibility was poor. Gradually, the water in the flooded area began to sink, making it no longer safe to make water landings with the Sea Otters. From now on they were also used for dropping goods.

All aircraft together made almost 120 flying hours from Valkenburg on this day, spread over 91 flights. They were performed by 31 aircraft. 149,000 sandbags, 84 dinghies, 3,360 liters of fresh water, 17,330 loaves of bread and 500 kilos of other food were dropped. On Wednesday, a total of 220 aircraft were involved in the relief effort, including 25 helicopters. Wednesday and Thursday were the busiest days at Valkenburg.

Thursday 5 February

The weather was still very bad this day. The cloud cover was between 300 and 500 feet and it was bleak and cold. The Fokker S.13 flew a mission to Walcheren from Valkenburg that morning, but near Hook of Holland almost collided with a Vickers Valetta of the Royal Air Force that was en route to Valkenburg together with a second aircraft. That day, four Valettas arrived at Valkenburg. In the afternoon, three Italian planes with relief supplies also arrived. The number of KLM Dakotas at Valkenburg was expanded to five, bringing the total number of aircraft operating from Valkenburg to 34, of which 12 were MLD.

The number of rescue flights from Valkenburg on Thursday was 83, with a combined flight time of 115 hours, during which 135,700 sandbags were ejected again. The Flying Boxcars ejected 88 large brand new life rafts delivered by the Valettas. Due to the bad weather, the number of flights decreased in the course of the afternoon.

During one of the flights, Sea Otter 12-3 had to make a precautionary landing on the Haringvliet. A Sea Otter also made a precautionary landing on the Hollands Diep.

Friday February 6

Like the previous days, it was still very cold on Friday morning. At ten o’clock C-47 X-1 of 334 squadron departed from Valkenburg with approximately 2500 kilos of cargo on board, which had to be dropped over the disaster area. At the start it appeared that there was something wrong with the control of the Dakota, but the machine could still gain height. At the end of runway 06 something went wrong and the X-1 made a belly slide, causing the right engine of the wing to break off. The Dakota was so badly damaged that the aircraft had to be written off. Fortunately, the crew got away with it. Most likely icing was the cause of the accident. Two more Catalinas of the Danish Air Force arrived from Denmark, with dinghies. The number of USAF C-119s had now been increased to six, making the use of the smaller aircraft redundant.

42 flights were made this day from Valkenburg, dropping 93,700 sandbags and 10,820 loaves of bread.

Saturday February 7 and beyond

The relief flights from Valkenburg were reduced from 7 February, but it would still take until 16 February before the last American C-119 departed. On Monday, most foreign aircraft departed from Valkenburg. The KLM Dakotas flew back to Schiphol. From now on, it was mainly flown by the Dakotas of the Netherlands Air Force and the Flying Boxcars of the USAF.

The evacuation of the victims of the disaster was completed on February 10, but that did not mean that the relief flights were over. The dikes still had to be closed and there were still areas isolated by the water. When an interim balance was drawn up on 10 February, it turned out that from February 2 a total of 419 flights had been carried out from Valkenburg Air Camp. The Americans with their C-119s accounted for most.

Tuesday February 10 was the last day that the Sikorsky S-51 was active over the disaster area. Pilot Idzerda flew the helicopter back to Valkenburg. Hundreds of people had been evacuated by helicopters in the previous week, 54 of whom were on the verge of drowning.

Foreign aid

At Valkenburg it was mainly the first week that foreign aircraft came and went. These were mainly American aircraft, but aircraft from the UK, Canada, Denmark, Italy and Norway also landed. The aircraft of these countries limited themselves to carrying the goods made available by those countries.

Great Brittain used Vickers Valettas and Handley Page Hastings for that supply. Canada sent Canadair DC-4M Argonauts and DHC.2 Beavers and Denmark sent PBY-5 Catalinas and B-17 Flying Fortress. At least three C-47 Dakotas came from Norway.

The very last foreign aircraft to arrive and depart were two Italian Air Force three-engine Fiat G.212s. These ancient planes had finally reached Valkenburg after a long journey via Nice and Paris. The goods donated by the Pope and the Italian government were unloaded, after which the old Fiats were declared non-airworthy. The crews then went to Amsterdam to await the message from the technicians that the aircraft could fly again. When that message came, the journey to Rome, via Paris, was accepted. That was long after the rescue operation was over.

When the scale of the disaster was known, the Dutch government also asked the U.S. for help. In response to this request, in The Hague, the U.S. Army created an organization to coordinate American aid. In good American practice, the American participation was codenamed: ‘Operation Humanity’. The contribution mainly consisted of nine Fairchild C-119C Flying Boxcars of the 317th Troop Carrier Wing. Nine aircraft were not constantly present, because changes also took place.

The planes with their double tail and square fuselage mainly dropped goods and empty sandbags. When the plane was over the dropping area, the tailgate opened and the load was literally kicked away by a few men. During one of these flights, a crew member had not properly clinged on and had fallen from the aircraft with the load. He would have survived because he ended up on his legs in a shallow muddy lake.

Finally

When air operations ended on February 16, 72,000 loaves of bread, 14,000 liters of fresh water, 13,600 kilos of food, 280 dinghies and 683,100 sandbags had been thrown from the planes, and the planes had consumed 400,000 liters of fuel and 4,500 liters of lube oil. It was a gigantic operation that had caused great activity at Valkenburg, but undoubtedly saved many human lives.

Jaap Dubbeldam thanks all those who helped in the preparation of this article.